I was a student in the Valley Stream Public Schools for 13 years. The single best thing they ever did for me was when they took me off Long Island for a week and showed me an Upstate New York winter.

It was the traditional trip to the Ashokan Center, the one my son didn’t get to take because the tradition ended sometime between my time in the Valley Stream schools and his time 41 years later. I’m gonna go out on a limb here and say the lawyers and insurance consultants got involved. But in February of 1975, way back before they ruined everything, two schools worth of sixth graders were loaded on tour buses and transported to a big camp near the Ashokan Reservoir in Olivebridge, NY, smack in the middle of the Catskill Mountains and smack in the middle of winter.

I was thinking about this trip when I was acclimating to the weather earlier this month up on Trisha’s Mountain. Embracing the cold, as my Buddhist friend likes to say. And Buddha, it was cold. The temperature only got above 30 degrees twice in 11 days, and then only briefly. It snowed on five of the days, and there was already two feet of snow on the ground when we got there. This of course didn’t stop Mookie from dragging me to the top of the backyard hill to sniff up every animal track immediately upon our arrival, which I expected. But he did keep looking back at me as if to ask why I, as God, had made this snow so deep and difficult for his little English Labrador Retriever legs to walk through.

Meanwhile, there were two things I remember from that 6th grade Ashokan trip.

One was the sheer exhilaration of flying through the air on a toboggan down a preposterously steep hill and whipping out across the frozen Esopus Creek, which is, coincidentally, the very same creek I was looking down on from a steep hill when I met Mookie in his breeder’s kitchen in nearby Saugerties 36 years later.

That toboggan ride is one of the single favorite memories of my life, and I always thought it was interesting that Lois Lowery chose sledding down a hill as Jonas’ first transmitted memory of the real life he was missing out on in the novel The Giver, a book I read with a lot of kids that never got to ride a toboggan down a hill and across a frozen creek and likely never would. I fully endorsed the experience, though, if they ever did happen to get the chance.

It was wild. When you hit the bottom of the hill, it was like being in a Hot Wheels car going through the speed booster, except you were propelled straight out across the ice instead of around the loop-de-loop. And don’t think that I don’t think of this image every Christmas Eve when George Bailey has to save his kid brother Harry. I’m gonna go out on a limb again here and say that the lawyers and the insurance consultants used that particular activity as Exhibit A when they finally put the kibosh on the sixth-grade trip.

The other thing I remember was winter.

I wanted to see if I could fill in some blanks about Ashokan, so I cast a net on Facebook and asked people who shared this experience what they remembered, and about 10 of them responded, God bless them.

Apparently I made a broom and a candle holder when I was there, and possibly a fire poker. I would have made a little man out of pewter, but somebody’s husband had broken the machine years earlier. I thought I had put on snowshoes for the first time in my life up on Trisha’s Mountain, but I’m told that my first snowshoe hike was 46 years earlier than that. Who knew.

One friend of mine, who went on to be a star pitcher on the Valley Stream South Falcons varsity baseball team, bravely recalled for us the memory of being such a homesick little wuss for the first two days of the trip that he required a full-scale intervention. As for myself, except for not wanting to poop in a public bathroom for the first two days, I don’t remember being homesick, but I probably missed TV, and Ace the beagle.

Another friend checked in, a guy I’ve known since kindergarten. In the interest of sharing the little details of life’s rich pageant that never cease to amuse and astound, I must tell you that this particular friend of mine happens to be a world-famous strongman who’s in the Guinness Book of World Records for rolling 14 frying pans into burritos with his bare hands in under a minute.

I pulled a couple of muscles in my ribcage opening the garage door last week. At the time, I thought my lung may have collapsed.

Not only did my old friend, a sweet, good-natured family man who is known in strongman competition circles as “The Crusher”, remember that the guys who set the toboggans up were named Kevin and Doug, and that another counselor named Andy challenged all comers to ice skating races, he was also able to pull up all the amazing pictures you see in this post in less time than I could have found last year’s tax returns.

The first pictures he posted were of us and our classmates, which were fun to see. Then he told me he had some other pictures, but they were of scenery rather than people. I asked him to send those pictures, too, and he did. You’d think I would have remembered that there were farm animals at the Ashokan Center, or that one of the counselors looked suspiciously like Richard Manuel of The Band, who had a place near the Ashokan Reservoir at the time.

What I did remember clearly as soon as I saw the pictures was the landscape, and the rickety old buildings dotting the snow and the bare trees stretched out across that landscape. Poking around the Ashokan Center website today, it looks like most of those buildings have been torn down and replaced. My broom and my fire poker are long gone, physically and in my memory, but the images of the countryside in winter that my friend probably took to finish up a roll of Kodak Instamatic film before we got on the bus back home are a direct match of the images in my mind’s eye.

I was eleven years old, and I was instantly charmed by winter in Upstate New York.

Now you can plainly see from the picture at the top of the post that my parents did not cheat when it came to keeping us dressed for the weather. That coat was as warm as a womb. There was an entire sheep sewed into that lining. And only fools go upstate in February without a good wooly hat and gloves. The picture doesn’t show them, but I’m sure I was wearing the sturdiest pair of boys’ brown leather waterproof hiking boots that JC Penney had on display that November. And I’m sure I had on a pair of long johns, which I still wear in the winter, as I’m still what my students in Rockaway amicably described as “one bony-assed motherf@#$er.”

It snows on Long Island, of course. Sometimes a lot. And the wind howls and the temperatures drop. And when it’s just a little too warm for snow, cold rain will come along and prick you with a million little needles. But in winter, it’s always just a smidge or so warmer in Valley Stream than it is in Copake Falls. The cold rain on Long Island is often snow in the Taconic-Berkshires. But the difference in what winter actually feels like in one place as compared to the other seems like more than a smidge, which we can define here as bigger than a tinge but smaller than a whit.

It feels like a different climate entirely.

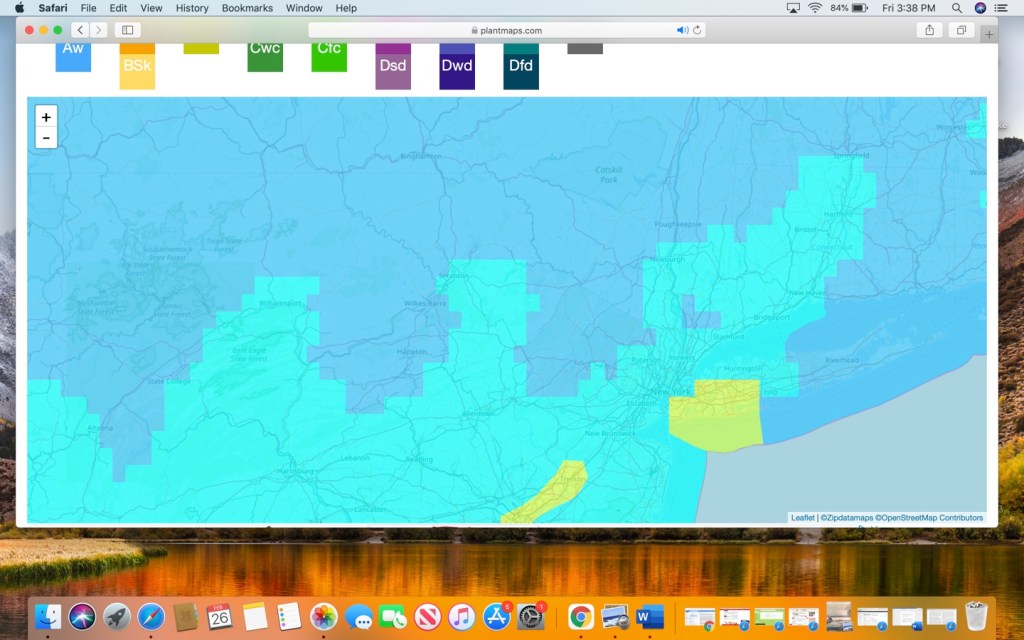

To see if there were any scientific data to back this up, I learned all about the Koppen Climate Classification System, something I’m positive that I was not taught in school, but I don’t remember making the broom, either.

According to several sources, none of them Wikipedia, Duffy’s Creek is in a Cfa, a warm oceanic climate, also called a humid subtropical climate. Trisha’s Mountain is in a Dfb, a warm summer humid continental climate. Some maps put all of Long Island and the Lower Hudson Valley in a Dfa, which is a hot summer continental climate. I can tell you that summers have been getting progressively hotter for twenty years in Copake Falls, which not only sucks, but would also suggest it’s probably well on its way to being classified as a Dfa climate. But the climate around New York City, which has always mostly sucked, is forever at the mercy of the Atlantic Ocean, so Cfa would be the more accurate classification.

The difference between these climate classifications comes down to the number of days of sustained cold temperatures. It’s slightly colder upstate. There I proved it. Thank you Herr Koppen.

But there’s way more to it than that.

I have no scientific proof of this, and I’m too lazy to find any, but there are more days of stillness in upstate winter, more days when the wind isn’t blowing at all. While we get less snow and less deep cold on Long Island, it seems like the wind rarely takes a day off, and it accompanies every snow and rain event just to add to the misery.

Up in the country, you can catch a stretch of days where even if it’s only 10 to 15 degrees in the afternoon, there’s no wind at all. When you put that together with a light falling snow or some blue sky, some clean, fresh mountain air and a foot or two of snowpack to muffle all the noise except for that satisfying crunch under your boots, you got yourself some magic weather.

On the first morning of our February vacation on the mountain, my rectangle informed me that Mookie and I would be greeted outside by six degrees Fahrenheit with a 10-15 mph wind, making the “real feel” (what your daddy called the wind chill) a robustly negative seven degrees. The sun thermometer on the back porch, which is more form than function, announced a Good Morning Copake Falls temperature of zero degrees. But while it stayed cold, the wind calmed down after the first couple of days, which was a beautiful thing, as Trisha’s Mountain has its own little microclimate, and in the warm months we suddenly get attacked by swirling 20 mph winds for no apparent reason. When it stops, its absence creates a loud silence.

And since Mookie was working so hard to trudge up the hill through the snowpack in the yard and back down the hill through the adjacent cornfield, we did a lot of our walking along on the blessedly level Harlem Valley Rail Trail, where the snow had been already been snowshoed, cross-country skied and otherwise tamped down a bit.

But even with all this evidence of human activity, a lot of time we had the whole thing to ourselves, which was both incredibly peaceful and a little bit frightening. First off, there was a lot of poop along the trail, and I know the good citizens of the Roe Jan Valley overwhelmingly clean up after their dogs, so it could have been anybody’s poop. It occurred to me that a couple of hungry bad ass coyotes or mountain lions could be somewhere up there in the woods, with one saying, “I’ll take the one with the fur, you take the tall duck.”

And if we were a good ways up the trail and one of us suddenly pulled a hamstring or were otherwise unable to walk, the other would be pretty screwed. One scenario would involve a panicking, breathless 130 lb. man carrying a wriggling, confused 102 lb. dog and the other would be an equally confused dog searching frantically for someone with thumbs who can drive an Outback.

Plus of course, severe cold weather can kill you. There’s an extra risk in traveling in winter, as your troubles would be significantly more complex if you found yourself suddenly not traveling. And once you get where you’re going, there are also power outages to consider, which is why in a future chapter we’ll learn all about Generac.

Add in the risk being further away from places you might need to get to in a hurry, hospitals in particular, through potentially pitch-dark, black-iced roads, and you could see why, just out of curiosity, I visited the website of an assisted living community across the border in Lenox, Mass.

This was actually when I was in the kitchen on the mountain, warming up from the second time that day I had swept the snow off the entire driveway. In comparison to some of our fabulously wealthy neighbors with mile-long driveways further up the mountains on Breezy Hill Road, our driveway is nothing fancy. But it’s still over a hundred feet, mostly uphill. One of our neighbors owns a landscaping and plowing business and we’re all very happy that we met each other. But he only plows and sands the driveway if there’s more than three inches of accumulation. Not being a full-fledged country guy yet, I don’t have a snow blower, which meant that the “nuisance snow” (a term I learned from Albany TV News), which fell for four days in a row, had to be either shoveled or swept, then sanded by hand before it turned the driveway into an Olympic ski jump.

To paraphrase Steven Wright, it’s a small world, but I wouldn’t want to sweep it.

When you sign up for upstate, winter owns you for four or five months out of every twelve. My darling wife, raised in a culture where people roasted in the sun on Point Lookout Beach four or five months a year, jokes that she has no idea what she was thinking.

But we both know. For every challenge that upstate winter presents in a place with fewer people and more hills, it more than rewards the survivors by enveloping them in its charms, its peace, its oxygen and its stunning natural beauty. Crunching through the snow along the Rail Trail, my mind was clear and easy enough to float me all the way back to that week in Ashokan, when I first experienced a wide open, heaven-sized country landscape under a quiet falling snow, and a clear and silent 15-degree blue sky morning amid rolling hills lit up with twinkling crystals.

Yes it can be bleak. Lots of cloudy days to get through. One of the first things I noticed at the house on Trisha’s Mountain this month was that, since we haven’t gotten up to putting color on the walls yet, both the inside and outside color palette was an endless loop of brown and white, broken up only by rows of red-twig dogwood on the tree farm and a few big evergreen trees visible from the windows. But winter never lasts forever, and that bleakness is what makes the greens and the yellows truly beautiful when they show up in April.

All the houses in Copake Falls, and all through the Dfb climate, look very serious about their jobs in the winter. And you can see houses that you can’t ordinarily see though the leaf cover. I can’t describe light through leafless trees in winter any better than Warren Zevon did when he said it looked like “crucified thieves”, so I won’t even attempt it.

The houses are working very hard to keep their owners warm. No lace curtains billowing in the windows and no whirligigs spinning on the front lawn. This is crunch time. Sometimes when I see or smell the fires from the chimneys of these hundred-and-fifty-year-old houses, I think of the people who settled places like this, who couldn’t crank the thermostat up, and for whom a fireplace could be the difference between life and death.

But despite the lurking dangers of winter, Mookie and I got to live our best life out there in the sharp and cold, here and now air, crunching through the snow along the Rail Trail. If it’s peace and quiet and a Zen feeling of no time and no self that you’re after, a trail through upstate winter woods is the place to be, particularly if you don’t have to get to a job.

On one of those clear mornings, we literally walked into a flock of bluebirds. At least twenty of them, dancing and singing through the trees on either side of us. This moment now lives alongside others in my life where I witnessed something so beautiful that I said to God, out loud, smiling, “you gotta be kidding me, man!”

Though God has a sense of humor, when it comes to nature’s wonders, he’s dead ass. He arranged for a flock of bluebirds to come along and flitter through the trees that morning because he really thought that Mookie and I should see them, just like he arranged for a sunset to bathe the stalks of last years’ corn and the sweep of snow down the hill in an ethereal orange glow as my son and I snowshoed across the field late that afternoon. All we had to do was dress for it, and there it was.

When people tell you not to waste your life away, they’ll sometimes tell you that we only get so many summers. Make hay while the sun shines and all that. Conversely, we only get so many winters. And because we needed all the oil and the plastic, winters are not what they were in 1975. I’d likely meet the bottom of the Esopus Creek if I took that toboggan ride today, and I’d need the Crusher to pull me out.

So while it is a great time to enjoy the couch, catch up on books or naps or watch a little basketball, you’ve got to get out there and embrace the winter while it’s here, lean into its big shoulders, draw in its icy breath and let it embrace you back.

The day before we rolled down the sandy driveway on Trisha’s Mountain and back down to Duffy’s Creek, we got two inches of fresh snow upstate. But it was one of those occasional storms where Long Island gets a few more inches than Copake Falls. That snow stuck around for a few days, then started melting into patches. When the last patch started melting in the backyard on the creek, Mookie made sure to roll on his side and make a dog angel, and I made sure to crunch through it with my brown waterproof boots.

It’s a long, hot summer, and we just needed a little more of that real feel before winter got away.

Copyright 2021 by John Duffy

All Rights Reserved